The following is an overview of how humans have achieved unique status on Earth, with the dominant societal narrative’s typical positive spin. In subsequent posts, I cover the dark side of the same story. Together, they’re a potentially-tedious (sorry!) introduction to the foundational concepts in the remainder of the Primer.

"No creation story is a myth to the people who tell it."

Performance Enhancements

Although many species use tools, humans are unique for the degree to which they use material beyond their own bodies to …

augment their natural abilities:

fire1 allowed us to claim for ourselves calories that we would not have otherwise been able to stomach, and that other species would have accessed instead

clothing serves as fur to protect us from the elements

knives serve as claws

eyeglasses (and binoculars and satellites) improve our vision

medicine and surgery help us overcome illnesses that our immune systems alone cannot fight

vehicles enable us to be many times speedier than we are on foot, and global supply chains deliver calories long distances from their origins to our mouths

communication technologies from the written word to Zoom allow us to transmit ideas across space and time

records and computing supplement our brains

manipulate our environments:

when it’s dark, humans have light

when it’s uncomfortably (or even dangerously) cold or hot or stormy, humans stay “room-temperature” and dry

when outside air is smoky, humans breathe purified air

when humans want Earth to yield more calories for their consumption, our “Haber-Bosch process”2 doubles our supply of edible energy

Catton encourages us to see these technologies as "external supplements to [our] own organic equipment". They’re extensions of our bodies. And the energy required to bring them into existence and operate them is an extension of each individual’s metabolism. The way in which today’s humans survive and the role that they play within their environments is so different from the clans of Homo sapiens who lived 200,000 years ago that we could qualify as a distinct species. Catton suggested the term Homo colossus.

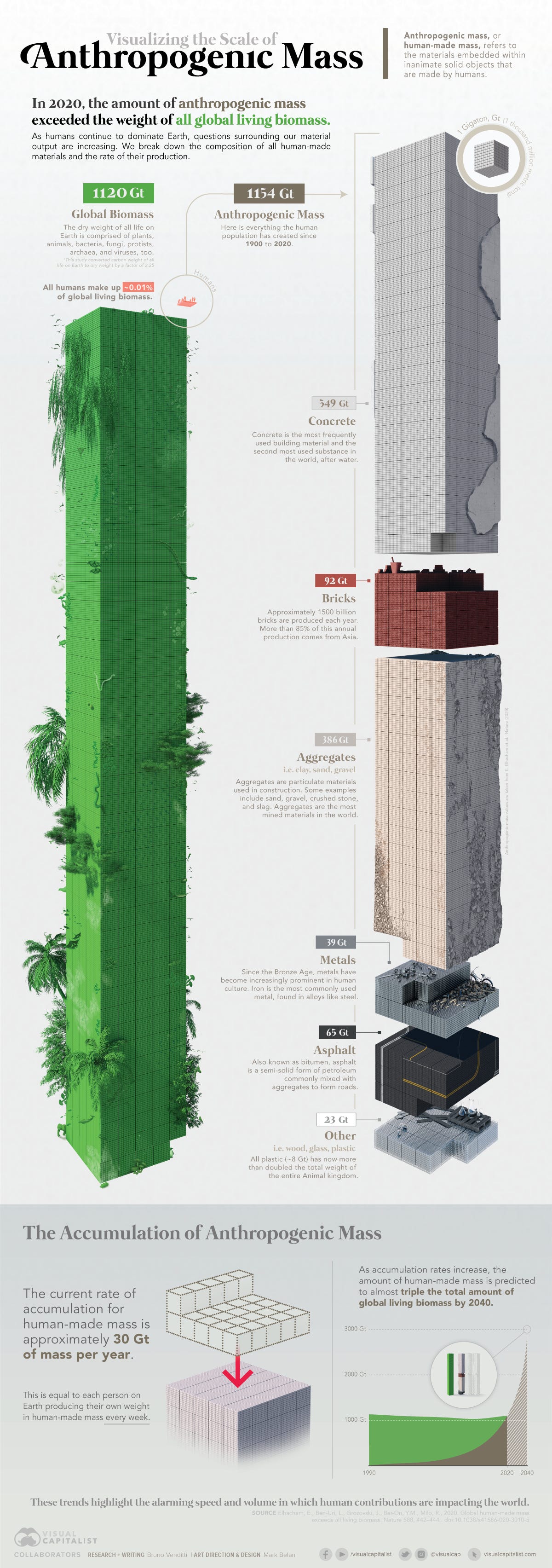

Many humans whose lifestyles are not luxurious have a super-naturally high metabolism, as a result of their on humans’ global nutrient network. We’re like dramatic versions of hermit crabs, capturing so much material as our prostheses that their mass now equals the weight of all biomass on Earth. We are our buildings, our tractors, our shipping containers, our bulldozers. (In subsequent posts, I’ll explore why these assets ultimately turn out to be critical liabilities.)

photo source, source, source

Ultrasociality

In “The economic origins of ultrasociality”, Lisi Krall and John Gowdy explain:

“Ultrasociality refers to the social organization of a few species, including humans and some social insects, having a complex division of labor, city-states, and an almost exclusive dependence on agriculture for subsistence.”

“Once underway, this [agricultural] transition was propelled by the selection of within-species groups that could best capture the advantages of (1) actively managing the inputs to food production, (2) a more complex division of labor, and (3) increasing returns to larger scale and larger group size.”

Agricultural societies, unlike hunter-gatherers, were able to produce a surplus. Their lifestyle required that they establish static settlements. During leaner years, the surplus served as back-up so that they didn’t have to face a die-off or leave their home territory in search of calories. With more people surviving, the harvest buffer had to increase, which led to more people, and so on. With greater food security, they got busy performing new roles, building large collective projects and accumulating possessions.

To appreciate how only a high population and specialization, in combination, make new forms of production possible, consider that 8 billion humans attempting to make bicycles -independently, from scratch, by hand- would result in zero bikes and 8 billion people dead of exhaustion and starvation. But if a portion farm for everyone, while others mine and others weld, etc. - we churn out about 364,000 bikes per day.

Humans’ Energy Boondoggle

In the mid-1800s humans discovered concentrated fossil-hydrocarbons. It took 196,000 pounds of plants (mainly algea and plankton) buried for 300 million years to form 1 gallon of liquid fossil-hydrocarbons.

Today, although only 3.4 billion humans are in the global workforce, with our fossil-hydrocarbon “energy slaves” (Buckminster Fuller’s term) we now accomplish the work of 500 billion3 people every day.

Net energy is what’s “leftover” after energy extraction. It powers the other activities that we associated with more “advanced” civilizations. If there’s little different between the amount of energy that you expend to hunt an animal and the amount of energy that you obtain from eating it, you don’t have much left to build temples. Machines allowed humans to get more-for-less, leaving them with spare capacity for “higher pursuits”. When humans first discovered oil, the high pressure sent it spewing from the ground, so they were able to collect abundant fuel with relatively little effort.

Net energy per capita is likewise a useful indicator. White’s Law states that "culture evolves as the amount of energy harnessed per capita per year is increased, or as the efficiency of the instrumental means of putting the energy to work is increased". I might know that a civilization extracts X units of fuel per year, which is enough to power tractors that harvest food for 6 billion humans. But if I want to know whether that civilization is thriving and composing operas or facing horror, I need to know whether it has 5 billion citizens or 12 billion.

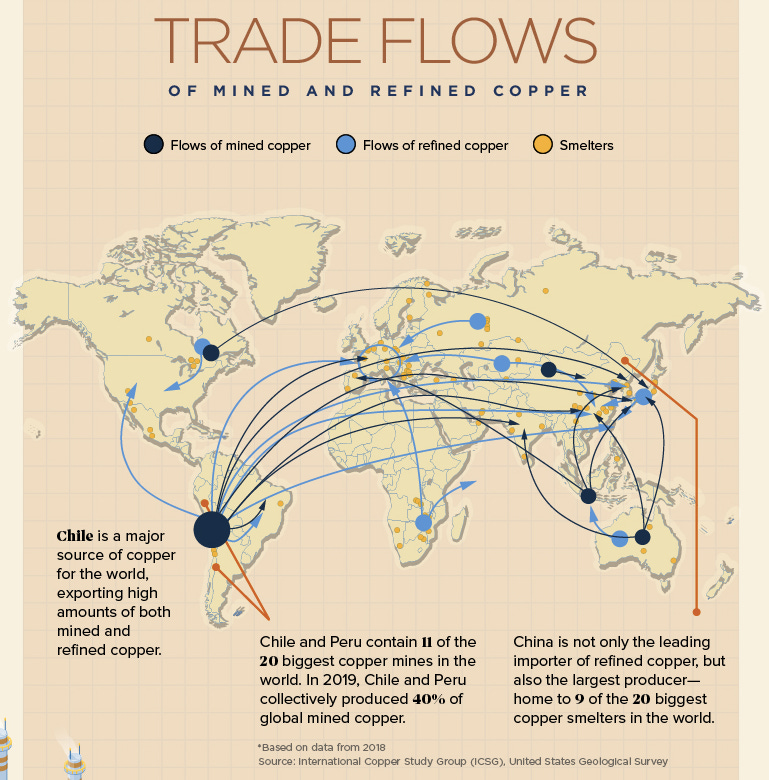

*Development and Progress*

Our abundant energy slaves are the prerequisite for the goods and services that boost our “standard of living”. We frequently take for granted how much work goes into powering the machines around us. Our enormous team of invisible energy slaves (especially the dense energy derived from fossil-hydrocarbons) do the heavy lifting. They provide our food so that an unprecedentedly large portion of our society can spend their days as lawyers, construction workers, therapists, software designers and artists. An individual can work in these occupations only if they aren’t busy obtaining food, and they aren’t busy obtaining food because someone or something else is working double-duty to do it for them. Our energy slaves also extract the copious raw materials that turn our ideas into physical reality.

Macroeconomics classes typically learn the Cobb-Douglas function (Y=AL2/3K1/3) where “A” represents Solow’s residual. Economists observed a substantial variation in output that neither population growth nor capital growth could explain. So “A” is a placeholder for this crucial mystery input, and economists teach that it’s an abstract factor like innovation. In fact, it’s industrial energy. After all, as Steven Keen explains, that “Labour without energy is a corpse. Capital without energy is a sculpture.” What we refer to as an increase in “worker productivity” could often be understood instead as the assignment of multiple invisible helpers.

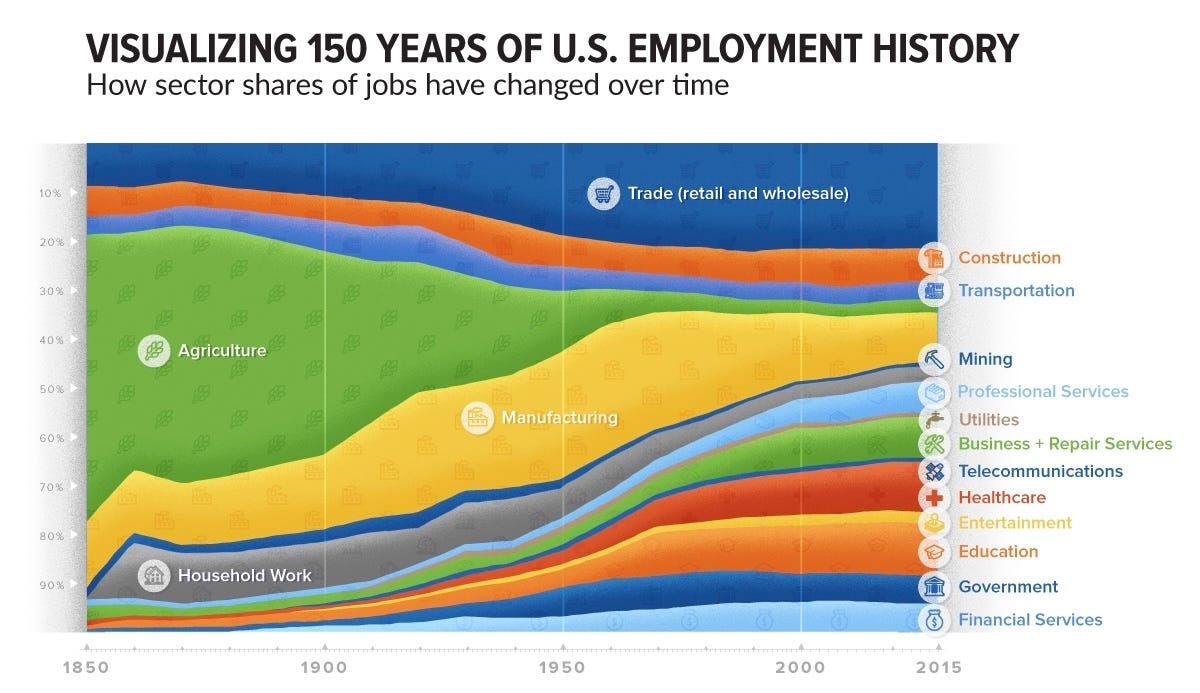

Human livelihood trends - In 1790, the contemporary concepts of employment and jobs didn’t yet exist, but 90% of Americans lived on farms, and we can assume that they were farmers or involved in farm-adjacent trades. The Post-Carbon Institute likewise notes that 75% of preindustrial societies’ populations engaged in farming. With agriculture, and then the discovery of plentiful fuel, we’ve been able to power a vast number of machines for the vital task of food production. Today only 1.2% of Americans farm. By a preindustrial peasant’s standards, much of what qualifies now as work would look like leisure. We can afford to be irrationally wasteful, burning the equivalent of 10 calories to obtain 1 calorie of food.

Human settlement trends - As machines replaced humans on farms, people had to seek employment to support themselves, and that income was to be earned in cities. Because cities have paved over their “fair share” of territory, they depend on distant areas to supply their basic needs. Much like capitalism pumps wealth to the top, urban environments survive only by “draining the periphery”. The USA accomplishes this via 25,000 miles of waterways, 95,000 miles of railroad, and 4,000,000 miles of highway.

Steve Keen interviewed by Rachel Donald

Steve Keen interviewed by Nate Hagens

an article on what constitutes a “luxury economy”

Here’s George Carlin’s stand-up routine about humans and their unmatched STUFF. Through participation in an empire's ultra-sociality-supported high-metabolism material resource extraction, humans accumulate STUFF. Elephants and owls and worms don't have this astounding trove of STUFF, nor do they build shelters that are many times the size of their bodies.

Some bird species might set fires intentionally as a hunting tactic, but a key difference between them and humans is that their “total caloric and material consumption per planet” hasn’t ballooned like ours has

The Haber-Bosch process combines N2 (which makes up 78% of our atmosphere) and CH4 (methane, usually from the fossil-hydrocarbon that we call “natural gas”) to make NH3 (ammonia, which conventional industrial agriculture uses as fertilizer)

Nate Hagens proposes the 500 billion estimate here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800919310067

You could also try to calculate how many “energy slaves” we exploit based on:

globally, civilization burns 600 quadrillion Btu global / year

humans burn 2200 calories/day = 92 calories/hour

a real human employee works 40 hours/week * 52 weeks/year

So the logo….is this your suggestion for the eco v stick-and-poke tattoo? 😂